The Fight Against Wisconsin’s Iron Mine

Tribal leaders, environmentalists and local officials have united to fight a massive mine which could be toxic to a water-rich area known as “Wisconsin’s Everglades.”

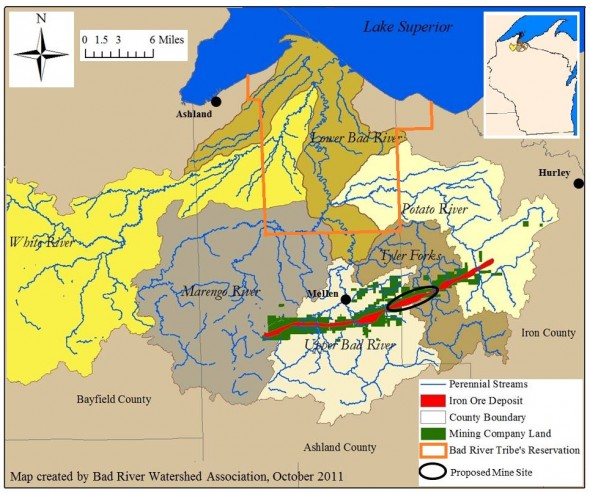

The water-rich Penokee Hills of northern Wisconsin are two parallel ridges that rise 1,200 feet above nearby Lake Superior in a scenically spectacular region. Over 200 inches of snow falls on the Penokees each year, providing plentiful clean water for the Penokee aquifer, the waterfalls in Copper Falls State Park and Lake Superior. The surface and groundwater that flows off the Penokee Hills feeds several major rivers (the Bad, Marengo, Montreal, and Brunsweiler) and provides drinking water for the city of Ashland and nearby towns. The water also feeds the Kakagon/ Bad River Sloughs where the Bad River Ojibwe Tribe maintains the largest natural wild rice bed in the Great Lakes basin. Forty percent of all the wetlands on the Great Lakes are on the Bad River Reservation. This wetland complex has been called “Wisconsin’s Everglades.”

Now imagine a mountaintop removal operation, which blasts the top off the Penokee Hills to extract a low-grade iron ore deposit hundreds of feet below. This would create the largest open pit iron mine in the world, some 4 miles long by l.5 miles wide and 1000 feet deep. Over a billion tons of waste rock and tailings created during the projected 35-year life of the mine would be dumped at the headwaters of the Bad River watershed where it could leach toxic metals into the largest undeveloped wetland complex in the upper Great Lakes. Seventy-one miles of rivers and intermittent streams flow through the proposed mining area, emptying into the Bad River and then into Lake Superior.

This is the scenario envisioned by Gogebic Taconite, part of the Cline Group, run by coal magnate Christopher Cline, who owns large coal reserves in Illinois and West Virginia. Cline has been cited 53 times over the past three years for violating water quality standards at his Illinois coal mines. United against this proposal, and in defense of the water, is an alliance of Indian tribes, environmental and conservation groups and local communities downstream from this massive mine. They agree with the vision statement of the Lake Superior Binational Forum: “Water is life. The quality of water determines the quality of life.”

The Penokee Hills. (c)Derek Johnson

During Governor Scott Walker’s 2013 State of the State address he brought out the state flag and pointed to the image of the miner on the flag and proclaimed that Wisconsin is a mining state. “If any state can move forward with a way to streamline the process for safe and environmentally sound mining, shouldn’t it be the Badger State?” Walker has proclaimed that his proposal is all about creating jobs. But his campaign received about $11 million from mining interests and Walker met with Gogebic lobbyists to draft an iron mining bill immediately after taking office in January 2011.

Walker’s evocation of “badgers” mining the state in its early days omits the fact that this was often made possible by the dispossession and impoverishment of the Native Americans who occupied mineral-rich lands before Wisconsin became a state. With the passage and signing of this new iron mining bill, Wisconsin begins the latest round in this long history of extracting natural resources from the lands of tribal people. For more than a century, these tribes lacked the legal power to fight the state. But in recent decades tribal groups, often allied with environmental groups and local officials concerned about the impact on tourism, have been able to defeat the mining interests. Tribal groups have become the most important protectors of water quality in Lake Superior region, and are likely to fight this new mine in the courts as well.

What a great article about a critically important issue. Let’s hope that the wider media takes advantage of Professor Gedicks’ research and analysis and makes it known to a wider audience.

This helps people understand how much is at stake for the health of our waters.